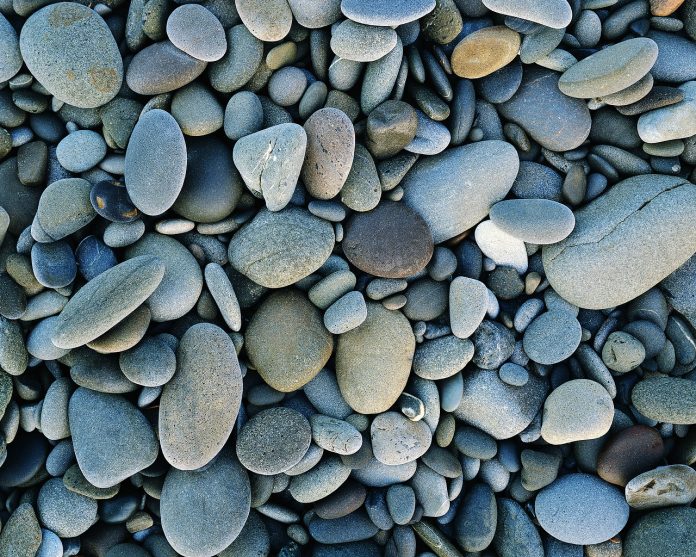

“Sticks and stones may break my bones but names will never hurt me.”

It was a saying we used when we were kids, to push back against nasty comments made by other kids. Many of those comments were directed at our ethnicity, or the fact that we were pohara (poor) in the eyes of our Caucasian classmates. But when it came to name calling, the words from the wahanui of smallminded, mean-spirited tamariki were cutting – and they did hurt. However, we would never give them the satisfaction of knowing it.

What further galvanised our resolve was that we were rich in everything else other than money, and that was the currency we were taught by our ancestors to measure one’s success in life.

Fast forward to today and now we have the added insult instrument of answerphones, tweets and Facebook – and its keyboard warriors – to add to the arsenal of derogatory darts they can randomly fire off without taking the time to think about the hurt their kino korero (hurtful comments) can cause.

A wake-up call

Recently we have witnessed a huge wake-up call to what happens when random, racist comments are made by keyboard warriors and salespeople who may have to answer for their racist answerphone message for the rest of their lives.

The fallout was catastrophic for two families, their community and a local company built on the cornerstone of community care, as was the case when we needed a vehicle seven years ago to ferry the homeless from one whare to another.

Fixing what’s broken

The real story is what has happened since the fallout and the first steps made to reconcile the hurting families. This began with all of us sitting at a table face to face beneath a korowai of forgiveness.

Thankfully, I went with a wise old kaumatua who knows more than a thing or two about life and the currency of its success being mana and not money – and other taonga you will never find on Facebook or Google.

His karakia (prayer) and his korero reached across the table in a language the hurting whanau and their gifted mediator could understand, and from that moment, an aura of aroha settled Sticks and stones on us and guided the two families together.

What will stay with me has nothing to do with keyboard warriors because, thankfully, I don’t do Facebook and I have never tweeted. I will leave this to the likes of tito Trump and his koretake Korean mate, who fire off derogatory darts like missiles, without thinking where they may end up.

Map of the human heart

What will remain in my mind has nothing to do with sticks or stones but everything to do with the true map of the human heart and what happens when a family humble themselves and front up kanohi ki te kanohi, seeking forgiveness.

Only time will tell if the apology was indeed pono (sincere). This is a private matter between the two families to settle.

For now, there are strong building blocks in place for a bridge of reconciliation. And to see such leadership on both sides – none more so than the wahine toa who has stood strong throughout – gives me great hope we can heal the hurts of not just individuals, but families, whanau and, according to Mandela himself, communities and a country.

When Mandela spoke on a Ngāti Whātua marae he said, “We must strive to be moved by a generosity of spirit that will enable us to outgrow the hatred and conflicts of the past. No one is born hating another because of the colour of his skin.” Wise words indeed.

We can all learn from this woman’s courage to stand up for what is wrong about the underbelly of racism in this country, and we can all learn about a pathway forward from our racist past, paved in forgiveness.

But it can only happen when we have the courage to face up to those who are hurting – kanohi ki te kanohi.

– By Tommy Kapai Wilson

“I write for this magazine because it plays a valuable role in our community to give people a voice.”